Respectus Philologicus eISSN 2335-2388

2025, no. 48 (53), pp. 74–86 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15388/RESPECTUS.2025.48.6

Patterns of Chinese Male and Female Poetry: the cicada image from the Pre-Qin period

(before 221 BC) to the Song Dynasty (960–1279)

Hanna Dashchenko

Academia Sinica, Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy

128, Section 2, Academia Rd, Taipei, 115, Taiwan

Email: annadashchenko78@gmail.com

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3432-3679

Research interests: Classical Chinese poetry; Female poetry of the Tang and Song dynasties

Abstract. The paper focuses on the patterns of Chinese male and female poetry with the cicada image from the Pre-Qin period (先秦, before 221 BC) to the Song dynasty (宋朝, 960–1279). The relevance of the study is determined by the dearth of works on the cicada image in classical Chinese poetry as well as by the gender bias. This paper fills in the underexplored aspect of the existing literature by tracing the evolution of the cicada image in poetry from the Pre-Qing period to the Song dynasty. The female perspective allows us to reveal the gendered patterns of cicada symbolism in classical Chinese poetry, deconstruct the processes of male dominance and restore the overlooked female contributions. The paper shows that in male poetry, the cicada is considered as a symbol of: 1) resurrection, longevity, and hope of rebirth; 2) hot summer; 3) people dissatisfied with their ruler; 4) an honest official; 5) purity. In female poetry, the cicada image is used as a harbinger of death; a symbol of an official who pursues his own goals and cares only about his benefit; cicadas’ chirping is associated with sorrow, longing, and anxiety. Two groups of female poems were identified depending on the way the emotions are depicted. The “implicit” group includes poems where the cicadas’ chirping becomes an eloquent detail and is associated with sorrow, longing, and anxiety. Still, the emotions of the lyrical persona are not directly mentioned. The “explicit” group includes poems where the cicadas’ chirping acts as a trigger for the uncontrolled emotional reaction of the lyrical persona.

Keywords: classical Chinese poetry; patterns of male and female poetry; cicada image; gender perspective.

Submitted 10 March 2025 / Accepted 15 June 2025

Įteikta 2025 03 10 / Priimta 2025 06 15

Copyright © 2025 Hanna Dashchenko. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License CC BY 4.0, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

The article aims to identify the patterns of Chinese male and female poetry with the cicada image from the Pre-Qin period to the Song dynasty. This period is divided into seven historical periods: the Pre-Qin period (先秦, before 221 BC), the Qin and Han dynasties (秦漢, 221 B.C.–220 A.D.), the Wei-Jin period (魏晉, 220–420), the Northern and Southern dynasties (南北朝, 420–589), the Sui dynasty (隋朝, 581–618), the Tang dynasty, Five dynasties and Ten kingdoms (唐朝 and五代十國, 618–960)1, and the Song dynasty (宋朝, 960–1279).

By “pattern” is meant a set of artistic devices, images, and themes used by male or female poets. It specifically excludes male imitation of the female voice from female poetry, i.e. poems written by men on behalf of a woman (Samei, 2004, pp. 30–35).

My choice of the cicada image is determined by two factors. Firstly, it is the very limited number of relevant studies in Chinese and English in comparison with those devoted to the other three of “Four Most Famous Insects” (四大名蟲): silkworms, locusts, and crickets. In particular, Chinese scholars mainly focus on the ambiguity of interpretations of “yongwu poems” (詠物詩詞) (Yao, 2016), the variety of feelings in such poems (Wang, 2012; Hu, 2012; Chen, 2017), the aesthetic aspects of the cicada image (Bai, 2005; Zhu, 2012), and artistic devices in the Han and Tang poetry with it (Su, 2011; Lai, 2023). Among Chinese studies in English, two works deserve attention. The first one is Wu’s research (2013) devoted to the reception of ci poetry with the cicada image in the early 20th century. The other one is Idema’s study (2019), where he distinguishes three groups of insect representation in Chinese literature. Secondly, the existing literature is also characterised by a lack of attention to the gender dimension. In particular, it shows the universalisation of male experience and male poetry and the appropriation of female contributions. This paper fills in this underexplored aspect by tracing the evolution of the cicada image in poetry from the Pre-Qing period to the Song dynasty.

The framework of the paper is feminist theory focusing on women as a marginalised group excluded from the mainstream literary process. As a result, the application of feminist theory allows revealing the gendered patterns of cicada symbolism in classical Chinese poetry, traces the genesis of female voices in extremely male-oriented Chinese literature, deconstructs the processes of male dominance and restores the overlooked female contributions.

Empirical basis. There are many Chinese poetry anthologies of different dynasties, themes, genres, etc. However, as they are limited in size, focused on a single topic or genre, and in most cases are dependent on the compiler’s individual opinion, it is impossible to complete a general list of all relevant poetry. At the same time, the existing electronic databases (THU Chinese Classical Poetry Corpus, 古诗文网, 搜韵诗词门户网站, etc.) are not only free from such shortcomings, but also allow using the search engine and classifying the relevant set of poetry according to selected parameters. Taking this into account, the 搜韵诗词门户网站 (Souyun Poetry Portal), the most comprehensive database of classical Chinese poetry, was used.At the time of the last access on November 01, 2024, it contained 357,386 poems relevant to the period under study: the Pre-Qin period – 607, the Qin and Han dynasties – 1,322, the Wei-Jin period – 3,798, the Northern and Southern dynasties – 5,236, the Sui dynasty – 1,511, the Tang dynasty – 57,032, and the Song dynasty – 287,880 poems.

Research methods. The methodology combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. To distinguish the main parameters of male and female patterns of poetry, fundamental content analysis was employed (Drisko & Maschi, 2016), allowing the reduction of the poetry corpus into easily quantifiable categories (e.g., male/female poet, cicada image, etc.). In this case, the selection and operation of these categories practically excludes the researcher’s subjective interpretations. Finally, it allowed for the distinction of two gender groups: male and female patterns of poetry (355,582/1,804 poems relatively). They were distributed by periods as follows: the Pre-Qin period – 607/0, the Qin and Han dynasties – 1,304/18, the Wei-Jin period – 3,772/26, the Northern and Southern dynasties – 5,225/11, the Sui dynasty – 1,510/1, the Tang dynasty – 56,190/842, and the Song dynasty – 286,974/906 poems. All poems written by male and female poets, whether real or mythical, were included. Male and female poems containing cicada characters that specifically referred to the insect were identified. Cases where cicada was mentioned as a part of jewellery (黄金蟬, 銀蟬, 玉蟬, etc.), a part of attire (蟬衫麟帶, 蟬冠, 金蟬, 蟬縠, etc.), or an inlay on musical instruments (鈿蟬) were not taken into account. In total, 3,669 relevant poems were identified (1.03% of the total number of poems in the studied period).

Narrative and poetic analyses were applied to interpret the quantitative parameters of female poetry patterns. The first one is widely applied in recent studies on classical Chinese poetry (Zhou, 2013; Dong, 2024). Its application allows us to trace the narrative environment (事境), through which the poets describe certain events in detail and reproduce emotions in their poetry. The second one focuses on the specific artistic devices, images, and themes in female cicada poems2 allowing the revealing of the patterns of cicada symbolism in female poems and comparing them with male ones. At the same time, the features of male poetry were established on the literature devoted to the cicada image in Chinese poetry in general, without their gender detailing.

1. The cicada image in male and female poetry: quantitative analysis

Table 1 shows the distribution of cicada poems by time period: the first column indicates the dynasty/period, the second – the number of male poems, the third – the number of female poems, and the fourth – the total number of poems.

Table 1. Number of male and female cicada poems (from the pre-Qin period to the Song dynasty)

|

Dynasty/Period |

Number of male cicada poems |

Number of female cicada poems |

Total number of cicada poems |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Pre-Qin |

9 |

9 |

|

|

Qin and Han |

23 |

1 |

24 |

|

Wei-Jin |

49 |

49 |

|

|

Northern and Southern dynasties |

93 |

93 |

|

|

Sui |

27 |

27 |

|

|

Tang |

961 |

5 |

966 |

|

Song |

2,497 |

4 |

2,501 |

|

Total |

3,659 |

10 |

3,669 |

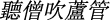

From a chronological point of view, most cicada poems were written in the Song – 2501 poems (68.17%). This can be explained primarily by the great number of the Song poems – 80.55% of the poems were written during the entire period. Percentages, i.e. the ratio of the number of cicada poems to the total number of poems written during a certain period, show us a different picture (see Fig. 1).

![[Despite the different lengths of reign for the dynasties (from 37 years to over 440 years), four periods account for more cicada poems than others: the Qin and Han dynasties, the Northern and Southern dynasties, the Sui dynasty, and the Tang dynasty. The percentage of cicada poems is significantly higher in these periods, sometimes more than twice as high (1.82% during the Qin and Han dynasties and 0.87% during the Song dynasty). Despite the largest number of cicada poems during the Song, they account for the smallest percentage of the entire study period. The reasons for such a sharp decline require separate study, but it can be assumed that it may be the rapid rise of the ci genre during the Song and the relevant changes in the use of poetic images.]](https://test.zurnalai.vu.lt/respectus-philologicus/lt/article/download/39324/version/35466/40597/125055/3.png)

Fig. 1. Cicada poems (from the pre-Qin period to the Song dynasty), ratio

2. Pattern of male poetry

The pattern of male poetry is revealed based on the available literary reflection on the cicada image, which is explained by two reasons: firstly, the limited size of the study not allowing to conduct the literary analysis of 3,659 male cicada poems; secondly, almost all available works, both general and specialized ones, concern exclusively male poetry, which can be partly explained by its quantitative predominance.

2.1 Resurrection, longevity, and hope of rebirth

The cicada image in male poetry is used as a symbol of resurrection and immortality (Williams, 2006, p. 93), regeneration and longevity (Werness, 2007, p. 87), and hope of rebirth (Idema, 2019, p. 39). Some of the earliest examples include Fu on the Cicada

( ) by Cai Yong (蔡邕, 132–192) and by Fu Xuan (傅玄, 217–278).

) by Cai Yong (蔡邕, 132–192) and by Fu Xuan (傅玄, 217–278).

This interpretation is the earliest one and is primarily associated with oracle-bone inscriptions of the Shang-Yin era (商殷, 1766–1122 BC) (Liu, 1991, p. 253) and jade amulets with the cicada image of the Shang dynasty (商朝, 16th–11th cent. BC). Since the early 20th century, Western scholars have directly linked the cicada image to the ancient Chinese beliefs about resurrection: “The dead will awaken to a new life from his grave, as the chirping cicada rises from the pupa buried in the ground. This amulet, accordingly, was an emblem of resurrection” (Laufer, 1912, p. 301). It is also confirmed by archaeological findings of the Zhou dynasty (周朝, 1046 BC–256 BC): jade amulets with the cicada image were placed in the mouth of the dead (Needham et al., 1976, p. 3).

2.2 Hot summer

Fu on the Cicada ( ) by Cao Zhi (曹植, 192–232) and by Sun Chu (孫楚, ?–293) as well as Fu on Catching Cicada (

) by Cao Zhi (曹植, 192–232) and by Sun Chu (孫楚, ?–293) as well as Fu on Catching Cicada ( ) by Fu Xian (傅咸, 239–294) are the earliest examples of male poetry where the cicada is a sign of a hot summer. The source of such an interpretation is The Seventh Moon (

) by Fu Xian (傅咸, 239–294) are the earliest examples of male poetry where the cicada is a sign of a hot summer. The source of such an interpretation is The Seventh Moon ( ) from Shijing (

) from Shijing ( , 11th–6th cent. BC), where its chirping marks the height of summer.

, 11th–6th cent. BC), where its chirping marks the height of summer.

2.3 Voices of dissatisfied people

In Decade of Dang ( ) in Shijing, the constant chirping of cicadas is compared to the clamour of people dissatisfied with their ruler. There are not many examples of this interpretation, and the earliest works can be traced to the Song dynasty: Suffering from the Heat (

) in Shijing, the constant chirping of cicadas is compared to the clamour of people dissatisfied with their ruler. There are not many examples of this interpretation, and the earliest works can be traced to the Song dynasty: Suffering from the Heat ( ) by Song Qi (宋祁, 998–1061), Shi Respectfully Presented to the Emperor in Honor of the Significant Destruction of the Western Lands (

) by Song Qi (宋祁, 998–1061), Shi Respectfully Presented to the Emperor in Honor of the Significant Destruction of the Western Lands (

) by Chen Deqian (沈德潛, 1673–1769), Letter of Anger (

) by Chen Deqian (沈德潛, 1673–1769), Letter of Anger ( ) by Wang Zheng (王拯, 1815–1876), etc.

) by Wang Zheng (王拯, 1815–1876), etc.

2.4 An honest official

In male poetry, the cicada image is an allegory for the official’s life and career. High-ranking officials tried to follow the principles proclaimed by the imperial family member and the prominent poet Cao Zhi, who is traditionally believed to depict himself in Fu on the Cicada. Its chirping is a sign of such an official: “The cicada cannot stop itself from chirping just as an honest official cannot but speak out when perceiving injustice or danger” (Idema, 2019, p. 47). If a poem says that the cicada does not chirp for some reason, it could be a hidden criticism of a certain official who does not express his opinion (Ibid., p. 46). The cicada image in such poems is considered a symbol of the official’s honesty and frankness (e.g., Fu on the Frozen Cicada ( ) by Lu Yun (陸雲, 262–303), Fu on the Chirping Cicada (

) by Lu Yun (陸雲, 262–303), Fu on the Chirping Cicada ( ) by Fu Xian (傅咸, 239–294), etc.).

) by Fu Xian (傅咸, 239–294), etc.).

2.5 Purity

Fu on the Cicada ( ) by Fu Xuan (傅玄, 217–278) is one of the earliest male poems where cicada is presented as a symbol of purity. The source of such interpretation is Fu on the Cicada (

) by Fu Xuan (傅玄, 217–278) is one of the earliest male poems where cicada is presented as a symbol of purity. The source of such interpretation is Fu on the Cicada ( ) by the outstanding female poet Ban Zhao (班昭, 49–120), who was the first one to dedicate a separate poem to this insect. She skillfully used the previous symbolic meanings of this image and added another dimension (purity), turning out to be perhaps the most popular one.

) by the outstanding female poet Ban Zhao (班昭, 49–120), who was the first one to dedicate a separate poem to this insect. She skillfully used the previous symbolic meanings of this image and added another dimension (purity), turning out to be perhaps the most popular one.

This interpretation of the cicada was particularly popular with those poets who, holding high state positions and being influential officials, “felt a need to stress their purity and innocence” (Idema, 2019, p. 41). At that time the aristocrats perceived the cicada through the prism of some features of its life: as it feeds only on dew, it was seen as divine or supernatural creature, and as it is not soiled with mud during the transformation from a larva to an insect, it was considered the personification of honesty and moral purity (Meng, 1993, p. 52).

Ban Zhao’s case is a good illustration of gender stereotypes in literature and literary studies. In Fu on the Cicada, she created a generalised image of this insect as a symbol of purity, which was later reproduced en masse by male poets. The data in Fig. 1 indirectly confirms it: the cicada image is most frequent during the Qin-Han period, after the new interpretation relevant to officials appeared. In addition, men borrowed not only this interpretation but also the title of Ban Zhao’s poem: there is not a single poem with the same title before it, but nine fu with such a title were written by men from the 2nd to the 10th centuries.

At the same time, Ban Zhao’s contribution is not discussed either in Chinese or English studies3. In this sense, the “simple” mention that she is “the earliest author known to have written a rhapsody about the cicada” (Idema, 2019, p. 46) or “这是一篇现在所见到的最早歌颂蝉的赋篇” (“This is the earliest extant fu praising the cicada”) (Quan Han fu pingzhu, 2003, p. 341) is symptomatic, as it says about the invisible appropriation of women’s contributions to a predominantly male field. At best, scholars point to her primacy in writing a poem on the cicada, but say nothing about the fact that she was the first to connect the cicada image with the social aspects of the officials’ work: purity, incorruptibility, and active civic position. In most cases, scholars do not mention her name and poem at all in their studies on Han fu (Qu, 1964; Gong, 1984) or the cicada images (Meng, 1993, pp. 45–56), although they list almost all the poets of that time and cite their works. It is a telling situation when commentators and scholars have no problem with tracing the origins of a certain image to Shijing written between the 11th and 6th centuries BC, but it is the problem to trace the sources of a popular image to the 1st century AD, especially given the obviously better preservation of documents and the relatively detailed information about Ban Zhao.

It is difficult to imagine that such an innovative male contribution would remain uncommented on and rewarded with a deafening silence4. Moreover, on the one hand, there is a tacit consensus not to refute her primacy directly, and, on the other hand, her contribution is first depersonalized (“From the late Han dynasty onward, the cicada, which was believed to feed on dew, established itself as a symbol of purity, and as such became a popular subject in the poetry of the third century and beyond” (Idema, 2019, p. 40)), and then there is an attempt to make Cao Zhi, a member of the imperial family born more than 70 years after Ban Zhao’s death, the source of this interpretation: “One of the finest (and most completely preserved) examples of such rhapsodies is a work by the princely poet Cao Zhi (192–232) <…> Once Cao Zhi had shown the way, other fu authors of the third and fourth century followed” (Ibid). Silence or even passive-aggressive denial is an example of patriarchal attitudes in the literary process.

3. Pattern of female poetry

The beginning of the female pattern can be dated back to the above-mentioned poem of Ban Zhao, who largely followed the existing literary tradition, which partially explains the reasons for reproducing her interpretation of the cicada image. She was a highly educated woman from a respected aristocratic family and played a pivotal role in the imperial court: Emperor He (漢和帝, 79–106) invited her as a tutor to the young empress and her ladies-in-waiting (Swann, 2001, p. XVII); she was a personal advisor to Empress Hexi (和熹皇后, 81–121), a regent and de facto a ruler having full control over the country during 106–121 (Ibid., p. 41); she was a mentor and then a colleague of the renowned male scholars and the famous commentators (Ibid., p. X). Their similar background allowed them to speak the same language, while gender differences allowed them to appropriate images and silence women’s contributions, which at the same time excluded other female poets with different life experiences from the process, making it impossible to reproduce the poetic tradition accurately.

The only exception to this pattern is ci to the tune Watching the Tide ( ) composed by the daughter of a military official from Poyang (鄱陽護戎女, ?–?), whose name was lost. She used the cicada as a sign of a hot summer, reproducing one of the elements of the male pattern. Describing the Dragon Boat Festival (端午節) on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar, she points out that 新蟬高柳鳴時 (“This is the time when young cicadas chirp high in the willows”). The other details allow us not only to see the celebration through a woman’s eyes, but also to hear all the sounds around her: the conversations of the young people, the noise of the dragon boat race, the splashing waves, the beat of drums, and the singing of the wind. The cicadas’ chirping is harmoniously incorporated into this masterfully depicted picture of the world.

) composed by the daughter of a military official from Poyang (鄱陽護戎女, ?–?), whose name was lost. She used the cicada as a sign of a hot summer, reproducing one of the elements of the male pattern. Describing the Dragon Boat Festival (端午節) on the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar, she points out that 新蟬高柳鳴時 (“This is the time when young cicadas chirp high in the willows”). The other details allow us not only to see the celebration through a woman’s eyes, but also to hear all the sounds around her: the conversations of the young people, the noise of the dragon boat race, the splashing waves, the beat of drums, and the singing of the wind. The cicadas’ chirping is harmoniously incorporated into this masterfully depicted picture of the world.

3.1 A harbinger of death

It is rather unexpected not to find out the cicada image as a symbol of resurrection, immortality, and longevity in female poetry, given traditional association of a woman with birth, and therefore immortality. Zhu Shuzhen’s (朱淑真, 1135–1180) gufeng Autumn Day Traveling ( ) gives this image the exact opposite meaning – it is a harbinger of death. At the same time, here we see a set of traditional images usually used by poets to depict a sad autumn scene evoking sadness and sorrow in the lyrical persona’s heart: wutong, withered leaves, dead trees, a cold western wind, geese flying south, and the cicadas’ chirping.

) gives this image the exact opposite meaning – it is a harbinger of death. At the same time, here we see a set of traditional images usually used by poets to depict a sad autumn scene evoking sadness and sorrow in the lyrical persona’s heart: wutong, withered leaves, dead trees, a cold western wind, geese flying south, and the cicadas’ chirping.

This gufeng is characterized by an unusual combination of three levels of imagery: the first one (lines 1 to 4) is a general description of an ordinary autumn day; the second one (lines 5 to 14) is a detailed depiction of the autumn scene with a step-by-step switching attention from what the lyrical persona sees (sky, water, clouds, birds, grasses, trees, and flowers) to what she hears (rain, wind, the sound of di, the cries of geese, the chirping of cicadas); and the third one (lines 15 and 16) is a philosophical reflections on the eternity of nature and the person’s place in the universe. These conventional parts also differ in the style and artistic devices. In the first part, we see a somewhat retrospective look at the changes in autumn with the personification of frightened (驚) wutong. The second part uses the montage technique starting with wide shots (the distant sky) that gradually transition to close-up (dew drops on a wilted lotus). In this part, Zhu Shuzhen also uses personification, making the lotus cry aloud (啼). The third part uses the principle of ambiguity (含蓄不露), opening up possibilities for several interpretations. These lines directly refer to seasonal changes in nature, and a person is also included in these cycles as a part of nature. Seeing the gradual dying of nature, the lyrical persona certainly knows that everything will bloom again in spring. However, her line 幾度榮枯新復古 can be interpreted differently: as a question about the past (How many times has this happened before?), or about the future (How many times are still yet to come?). It raises the question about the transience of human life itself compared to the universe and her place in it. At the same time, she mourns the dying of the beauty around her and her short life, as she may no longer see the renewal of nature and, in particular, the rebirth of the cicada next spring.

In this poem, Zhu Shuzhen skillfully combines visual and auditory imagery, which not only complement each other but also make the autumn scene more real. To make the visual images more vivid, she uses colours in combination with detailed description

(杳杳高穹片水清; 園林草木半含黄; 籬菊黄金花正吐). The sounds can be classified into five categories according to who/what makes them: a natural phenomenon

(蕭瑟西風起何處), a musical instrument (高樓玉笛應清商), a bird (天外數聲新雁度), an insect (池上枯楊噪晚蟬), and a plant (愁蓮蔌蔌啼殘露). She artfully incorporates a lyrical persona into the natural world, making her an integral element of the scene along with plants and animals.

Thus, Zhu Shuzhen’s poem radically changes the male interpretation. Instead of emphasising immortality, the cicada image indicates the transience of life, and its chirping can be seen as a harbinger of death (for both nature and a person). This approach is not just a negative denial of the male legacy, which could be seen as a continuation of dependence on the male patriarchal episteme in Chinese poetry. The female interpretation does not deny the value of the male one. Still, it adds an additional dimension to it in full accordance with the established and accepted method within Chinese literary tradition –

舊瓶裝新酒 (“to put new wine into an old bottle”). She combines traditional images to depict the autumn scene with a specific composition and various artistic devices, thus creating a new symbolic dimension of the cicada image. To express her feelings and experiences, she chose the way of rethinking the meaning of the cicada image created by men.

3.2 A selfish official

If the cicada’s chirping in male poetry is interpreted as a sign of an honest official who cannot tolerate injustice, in female poetry it becomes a sign of an official who pursues only his own goals and cares only about his benefit. Cicada ( ) by Xue Tao (薛濤, 768–832) shows a radical change in this meaning and a conscious demonstration of its inconsistency with the real state of affairs in society. At first glance, she praises the cicada in a traditional way and uses it as a symbol of honesty and frankness, popular among officials of the time.

) by Xue Tao (薛濤, 768–832) shows a radical change in this meaning and a conscious demonstration of its inconsistency with the real state of affairs in society. At first glance, she praises the cicada in a traditional way and uses it as a symbol of honesty and frankness, popular among officials of the time.

Xue Tao’s shi and Ban Zhao’s fu share several features, but their content differs. Ban Zhao’s fu praises this insect, and the subsequent poets adopted this image to depict purity, honesty, and sincerity. Modern scholars hardly comment on Xue Tao’s poem, sometimes pointing out its hidden meaning (Dong, 2009, p. 26). If commentaries are provided, it is interpreted only within the framework of the conventional theme of female poetry, namely separation from the beloved and longing for him. Researchers consider that Xue Tao depicts herself as the cicada; therefore, the last two lines, 聲聲似相接,各在一枝棲, are interpreted as a description of longing in separation (Dong, 2009, p. 23; Lu, 2010, p. 62) or sadness from loneliness (Su, 2008, p. 75). This interpretation neglects Xue Tao’s life and unjustifiably focuses on what female poetry is presumed to be from the researchers’ perspective.

Xue Tao is one of the “Four Greatest Female Shi Poets of the Tang Dynasty”

(“唐代四大女詩人”), whose poetry influenced both female and male poets. She was first a guanji (官妓, government courtesan) (Larsen, 1983, pp. 103–104). Still, at the age of 15, she became a yingji (營妓, barracks courtesan), a prostitute assigned by the government to military officials. It allowed her to get acquainted with two jiedushi (節度使, military governor), a number of high-ranking officials, and prominent literati (Ibid., p. 86). Jiedushi even petitioned the emperor to allow her to take up the position jiaoshulang (校書郎, library secretary), which had never been held by a woman before5.

Xue Tao wrote this shi as a person close to the military governor, held a government position, and had a long and specific experience communicating with officials. The researchers note that she was well-versed in civil service and the political situation (Dong, 2009, p. 22). She was also intolerant and contemptuous of incompetent officials, and in her writings, she ridiculed those who did nothing to solve problems in society (Ibid., pp. 20–21). The second half of her shi can be interpreted as a rather frank criticism of the officials: they seem to be engaged in state affairs, that is, act in the interests of the whole society, but each of them pursues his own goals and cares only about his benefit, neglecting the ideas of the common good and justice.

In this way, Xue Tao, firstly, points out that even though she is a woman from the lowest level of society, she managed to get the official position of secretary, and, secondly, she indirectly emphasises her purity and innocence, because she differs from the high-ranking officials around her. There is a clear contrast between the external and internal image: officials look dignified and noble outside, but they are distorted in pursuit of positions and fame inside, but the lyrical persona, on the contrary, is a prostitute outside, who is traditionally considered as the frivolous one without moral principles, but she is a noble and intelligent person inside.

This ironic view of the traditional image was caused by the marginal position of the female poet, who had the opportunity to observe the officials behind the scenes of their positions and compete with them, a priori having no chance of winning or taking a decent place in their world. Such a mismatch between talent and status, a mixture of resentment and envy, led to a relevant modality of her poetry that was not aimed at developing her own language, self-sufficient and valuable, regardless of male standards, but rather at ridiculing and humiliating male poetic means of expression.

3.3 Sorrow, longing, and anxiety

As in female poetry the cicadas’ chirping is associated with sorrow, longing, and anxiety6, the available poems can be divided into two groups – implicit and explicit – depending on the way the emotions are depicted.

The implicit group includes Listening to a Buddhist Monk Playing the Luguan

( ) and Western Cliff (

) and Western Cliff ( ) by Xue Tao, and Gongci. Poem 120 (

) by Xue Tao, and Gongci. Poem 120 (

) by Lady Huarui (花蕊夫人, 886–926). Choosing the form of seven-syllable jueju (28 characters), poets limited themselves in artistic devices, thus “<…>多为兴托之语, 贵意有象” (“<…> in most cases the lines have a hidden meaning, imagery is most valued”) (Qian, Liu, 2016, p. 12).

) by Lady Huarui (花蕊夫人, 886–926). Choosing the form of seven-syllable jueju (28 characters), poets limited themselves in artistic devices, thus “<…>多为兴托之语, 贵意有象” (“<…> in most cases the lines have a hidden meaning, imagery is most valued”) (Qian, Liu, 2016, p. 12).

In these jueju, the cicadas’ chirping is associated with sorrow, longing, and anxiety. Still, the authors do not directly mention the emotions of the lyrical persona: 曉蟬嗚咽暮鶯愁 and 夕陽影裏亂鳴蜩 by Xue Tao, and 捲簾初聽一聲蟬 by Lady Huarui. Though these poems are thematically different, they describe personal loss, depressed mood and death: the gradual dying of nature in autumn (Xue Tao’s  ), grief for the deceased and the invocation of his soul (Xue Tao’s

), grief for the deceased and the invocation of his soul (Xue Tao’s  ), and the fear of losing the emperor’s favour (Lady Huarui). The consonance of the negative emotions of the lyrical personae associated with the cicada image is interesting. The cicada itself is incapable of feeling anything and conveying any feelings, so poets endowed this image with various feelings (from delight and pleasure to regret and sadness) relevant to their mental state and perception of the world (Meng, 1993, pp. 53–55).

), and the fear of losing the emperor’s favour (Lady Huarui). The consonance of the negative emotions of the lyrical personae associated with the cicada image is interesting. The cicada itself is incapable of feeling anything and conveying any feelings, so poets endowed this image with various feelings (from delight and pleasure to regret and sadness) relevant to their mental state and perception of the world (Meng, 1993, pp. 53–55).

The explicit group includes Thinking [of the One] Far Away ( ) by Lady Lian

) by Lady Lian

(廉氏, ?–?), Sending to a Husband ( ) by Liu Tong (劉彤, ?–?), and On an Autumn Day [I] Climb the Tower (

) by Liu Tong (劉彤, ?–?), and On an Autumn Day [I] Climb the Tower ( ) by Zhu Shuzhen. Their specific feature is the explicit expression of female feelings and the direct connection between the cicadas’ chirping and the emotional pain caused by these sounds. This chirping acts as a trigger for the lyrical persona’s uncontrolled emotional reaction.

) by Zhu Shuzhen. Their specific feature is the explicit expression of female feelings and the direct connection between the cicadas’ chirping and the emotional pain caused by these sounds. This chirping acts as a trigger for the lyrical persona’s uncontrolled emotional reaction.

Lady Lian’s poem is a gufeng, an old-style poem written as an imitation of ancient poets with a clear and frank expression of the lyrical persona’s feelings. It gives the author the opportunity to explicitly express the emotions of a woman who has to live away from her husband for several years. The other two poems are seven-syllable jueju like those from the implicit group. As the balance between a level tone ping (平) and an oblique tone ze

(仄) in each line was one of the specific features of shi poetry, a poet had to follow a certain pattern while creating a poem. Liu Tong’s poem was written according to the “level tone beginning – level tone end” pattern (平起平收式) (Qian, Liu, 2016, p. 50) which was also used by Xue Tao in the above mentioned poem Listening to a Buddhist Monk Playing the Luguan, while Zhu Shuzhen followed the “oblique tone – level tone end” pattern (仄起平收式) (Ibid, pp. 48–49) which was also chosen by Lady Huarui two centuries earlier.

In these jueju, the cicadas’ chirping is directly associated with the sadness and sorrow of the lyrical persona spending all the time in her inner chamber. This chirping for her is the only connection with the world outside. Thanks to it, she knows about changing seasons, a poignant metaphor for the passage of time. However, unlike their predecessors, the Song female poets use these sounds to emphasise the helpless and extremely tense emotional state of the lyrical persona. Both authors use evaluative epithets with a positive emotional meaning to describe the scene (emerald silk, jade incense burner, evening light, high tower) and contrast them with lines where the lexical items with negative polarities are used (牽斷愁腸懶晝眠; 殘蟬淒楚不堪聽). This juxtaposition gives the text a special emotionally expressive colour and deepens the imagery of the poetic line.

Conclusion

This study has shown that the cicada image was one of the most popular images in male poetry from the pre-Qin period to the Song dynasty (3,659 poems, or 99.73% of the total number of poems with it). Although this image first appeared in female poetry in the 1st century, 90% of female cicada poems were written during the Tang and the Song dynasties. In general, female poetry is represented by 10 relevant works, which is 0.27% of the total number of poems with this image.

It has been found that the pattern of male cicada poems consists of five elements: 1) a symbol of resurrection, longevity, and hope of rebirth; 2) a sign of hot summer; 3) a symbol of people dissatisfied with their ruler; 4) a symbol of an honest official; 5) a symbol of purity. It has been revealed that the source of the latter interpretation is Fu on the Cicada by Ban Zhao, whose contribution to the interpretation of this image was appropriated by male poets and is still ignored by synologists.

Analysis of all female cicada poems revealed that the female pattern consists of three elements. First, the cicada image as a symbol resurrection, immortality, and longevity is questioned (Zhu Shuzhen): the lyrical persona mourns the dying of nature and her short life, as she may no longer see its renewal and, in particular, the rebirth of the cicada next spring. Thus, the cicadas’ chirping can be considered a harbinger of death. Second, the male interpretation of its chirping as a sign of an honest official acquires a different meaning in female poetry (Xue Tao): it is a sign of an official who pursues only his own goals and cares only about his benefit, neglecting the ideas of the common good and justice. Third, in female poetry, the cicadas’ chirping is associated with sorrow, longing, and anxiety. Depending on the way the emotions are depicted, two groups of works were distinguished. The implicit group includes poems by Xue Tao and Lady Huarui, where the cicadas’ chirping becomes a telling detail associated with the emotions described above, but they are not directly mentioned. The explicit group includes poems by Lady Lian, Liu Tong and Zhu Shuzhen, where the cicadas’ chirping acts as a trigger for the lyrical persona’s uncontrolled emotional reaction. These poems are characterised by using emotive words to elicit an emotional response from the reader.

Acknowledgments

This research is carried out within the framework of the project “Traditions of Chinese Rhetoric: Concepts, Formulations, Futures” (“無核心的傳統——帝制時期『中國修辭學』的多樣性”) for 2024–2025 under the supervision of Prof. Zeb Raft (Institute of Chinese Literature and Philosophy, Academia Sinica, Taiwan). The author acknowledges the financial support provided by the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (113-2811-H-001-015).

References

Bai, F. 白福才, 2005. Chan zai Zhongguo gudai shici zhong de shenmei yiyi蝉在中国古代诗词中的审美意义 [The aesthetic significance of the cicada in ancient Chinese poetry].  [Journal of Yan’an College of Education], 4, pp. 35–37. [In Chinese].

[Journal of Yan’an College of Education], 4, pp. 35–37. [In Chinese].

Chen, L. 陈丽君, 2017. Song dai yong chan ci yanjiu  [Ci poetry about cicada in the Song dynasty]. Master’s thesis. Dalian: Liaoning Normal University. [In Chinese].

[Ci poetry about cicada in the Song dynasty]. Master’s thesis. Dalian: Liaoning Normal University. [In Chinese].

Dong, N., 2024. A study on the narrative tradition of Chinese literature. New York: Paths Publishing Group.

Dong, X. 董乡哲, 2009. Xue Tao shige yishi  [Interpretation of Xue Tao’s poetry]. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe. [In Chinese].

[Interpretation of Xue Tao’s poetry]. Xi’an: Sanqin chubanshe. [In Chinese].

Drisko, J., Maschi, T., 2016. Content analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gong, K. 龚克昌, 1984. Hanfu yanjiu  [Study on Han fu]. Jinan: Shandong wenyi chubanshe. [In Chinese].

[Study on Han fu]. Jinan: Shandong wenyi chubanshe. [In Chinese].

Hu, M. 胡明霞, 2012. Tang shi chan yixiang yanjiu  [The cicada image in the Tang shi]. Master’s thesis. Wuhan: Hubei University. [In Chinese].

[The cicada image in the Tang shi]. Master’s thesis. Wuhan: Hubei University. [In Chinese].

Idema, W., 2019. Insects in Chinese literature: A study and anthology. Amherst: Cambria Press.

Lai, Y. 賴怡翎, 2023. Han Tang yongchan shifu de tiwu xiezhi yu renwu diangu

[The classical allusions of things and people in the Han and Tang cicada shi and fu]. Master’s thesis. Taipei: National Chengchi University. [In Chinese].

[The classical allusions of things and people in the Han and Tang cicada shi and fu]. Master’s thesis. Taipei: National Chengchi University. [In Chinese].

Larsen, J., 1983. The Chinese poet Xue Tao: The life and works of a Mid-Tang woman, Ph.D. thesis. Iowa City: The University of Iowa.

Laufer, B., 1912. Jade: A study in Chinese archaeology and religion. Chicago: Field Museum of Natural History.

Liu, G. 劉淦芝, 1991. Zhongguo chan xue fazhan. 中國蟬學發展 [Development of cicada studies in China]. 台灣昆蟲期刊 [Formosan Entomologist], 11 (3), pp. 252–259. [In Chinese].

Lu, Y., 2010. Readings of Chinese poet Xue Tao. Master’s thesis. Amherst: University of Massachusetts.

Meng, Z. 孟昭连, 1993. Zhongguo chong wenhua  [Chinese insect culture]. Tianjin: Tianjin renmin chubanshe. [In Chinese].

[Chinese insect culture]. Tianjin: Tianjin renmin chubanshe. [In Chinese].

Needham, J., Ho, P., Lu, G., 1976. Science and Civilisation in China, 5: Chemistry and chemical technology, 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Qian, Z., Liu, Q. 钱志熙, 刘青海, 2016. Shi ci xie zuo chang shi  [Basic knowledge on writing shi and ci]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [In Chinese].

[Basic knowledge on writing shi and ci]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [In Chinese].

Qu, T. 瞿蜕园, 1964. Han Wei Liuchao fu xuan  [Collection of the Han, Wei and Six Dynasties’ fu]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [In Chinese].

[Collection of the Han, Wei and Six Dynasties’ fu]. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju. [In Chinese].

Quan Han fu pingzhu  [Commentaries on all Han fu], 2003. Shijiazhuang: Huashan wenyi chubanshe. [In Chinese].

[Commentaries on all Han fu], 2003. Shijiazhuang: Huashan wenyi chubanshe. [In Chinese].

Samei, M., 2004. Gendered persona and poetic voice: The abandoned woman in early Chinese song lyrics. Lanham: Lexington Books.

Sou yun 搜韵–诗词门户网站. Available at: https://sou-yun.cn/QueryPoem.aspx [Accessed 1 November 2024].

Su, S. 蘇珊玉, 2008. Xue Tao ji qi shi yanjiu  [Study on Xue Tao and her poetry]. Taibei xian yongheshi: Hua mulan wenhua. [In Chinese].

[Study on Xue Tao and her poetry]. Taibei xian yongheshi: Hua mulan wenhua. [In Chinese].

Su, W. 蘇婉玉, 2011. Wan Tang shi chan yixiang yanjiu  [The cicada image in Late Tang shi poetry]. Master’s thesis. Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. [In Chinese].

[The cicada image in Late Tang shi poetry]. Master’s thesis. Tainan: National Cheng Kung University. [In Chinese].

Swann, N., 2001. Pan Chao: Foremost woman scholar of China. Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies.

Wang, L. 王丽丽, 2012. Chan sheng liu xiang, yuanyi qiliang: Tanxi yongchan shici zhong de beichou qinghuai  ——

—— [The chirping of cicadas, sorrow and resentment: Analysis of sadness and anxiety in cicada poems].

[The chirping of cicadas, sorrow and resentment: Analysis of sadness and anxiety in cicada poems].  [Yangtze River Delta (Education)], 4, pp. 63–64. [In Chinese].

[Yangtze River Delta (Education)], 4, pp. 63–64. [In Chinese].

Werness, H., 2007. The continuum encyclopedia of animal symbolism in art. New York: Continuum.

Williams, C., 2006. Chinese symbolism and art motifs: A comprehensive handbook on symbolism in Chinese art through the ages. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing.

Wu, S., 2013. Falling leaves and grieving cicadas: Allegory and the experience of loss in Song lyrics. In: Modern archaics: Continuity and innovation in the Chinese lyric tradition, 1900–1937. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center: pp. 45–107.

Yao, D. 姚道生, 2016. Yuefu buti yanjiu  [Study on Yuefu buti]. Doctoral dissertation. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Baptist University. [In Chinese].

[Study on Yuefu buti]. Doctoral dissertation. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Baptist University. [In Chinese].

Zhou, J. 周剑之, 2013. Song shi xushixing yanjiu  [Study on the narrativity of Song poetry]. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. [In Chinese].

[Study on the narrativity of Song poetry]. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe. [In Chinese].

Zhu, W. 朱晚平, 2012. Tang dai yong chan shi yanjiu  [Tang shi poetry about cicada]. Master’s thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University. [In Chinese].

[Tang shi poetry about cicada]. Master’s thesis. Nanjing: Nanjing Normal University. [In Chinese].

1 Hereafter I will refer to this period as the Tang dynasty.

2 Hereinafter the term “cicada poems” is used for poems featuring the image of a cicada.

3 The only exception is a passing mention that after the Wei-Jin period the number of cicada poems increased, so “此赋的影响是明显的 ” (“the influence of this fu is obvious”) (Quan Han fu pingzhu, 2003, p. 341).

4 The image of the butterfly seen in a dream can be an example. All commentators immediately refer to Zhuangzi (莊子, 369–286 BCE) as the source of it.

5 As a woman was never appointed to this position, some scholars questioned this information (Su, 2008, p. 33).

6 The cicada chirping can also be associated with such feelings in some male poems, but they can be considered as male imitation of the female voice (e.g., ci to the tune The Hermit by the River (

) by Gu Xiong (顧夐, 10th century), ci to the tune The Pride of the Fisherman (

) by Gu Xiong (顧夐, 10th century), ci to the tune The Pride of the Fisherman ( ) by Ouyang Xiu (歐陽修, 1007–1072), etc.). As some poems cannot be included into this category, a specific study is needed, which is beyond the scope of this work. It can be preliminarily assumed that such male poems differ from female ones thematically, focusing mainly on friendship, memories, and praising antiquity.

) by Ouyang Xiu (歐陽修, 1007–1072), etc.). As some poems cannot be included into this category, a specific study is needed, which is beyond the scope of this work. It can be preliminarily assumed that such male poems differ from female ones thematically, focusing mainly on friendship, memories, and praising antiquity.